Lerner Student Center

Current Status: Finished October 1999

Construction: $78,000,000 Architects' Fees: $806,000.

Columbia's old Ferris Booth Hall (1957) was ugly and, with only 75,000 square feet, far too small. The new 225,000 square foot student center should remedy this by the Fall of 1999. Construction will take 3 years because work hours have been restricted to minimize the disturbance to undergraduates living in adjacent Carman Hall. This building represents a major part of Columbia College's push to improve its rankings, and its $50 million-plus cost is forcing the college to expand, causing new construction elsewhere in the neighborhood. The originally proposed design was for a very square modern building that made little effort to harmonize with its historic milieu. To be fair to the architect, Bernard Tschumi (picture), this was understood to be only a very rough draft. Thanks to community response to a poster campaign during the summer of 1996, some significant positive changes have been made. Here is Columbia's own story about the project. An early proposal.

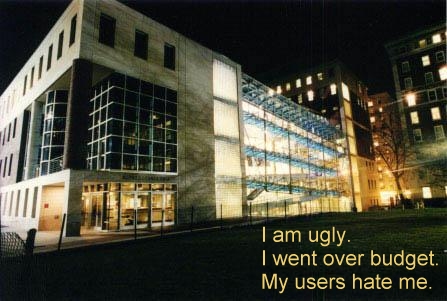

The final product, campus side and Broadway side.

.

The current proposal adds a green copper (or copper-colored) roof to the design and makes the facade more harmonious with Butler Library and the rest of campus. Unfortunately, this roof will be of the steep-pitched and hollow kind seen on fast-food restaurants, rather than one like the other buildings on campus, and there is some possibility that it will not be a roof at all, but will contract to a mere block-like casing for the climate-control equipment. The building will also suffer from a vast glass wall facing campus, which threatens create a glitzy high-tech spectacle, revealing ramps and staircases full of students, that is out of character with the traditional buildings of campus. On the positive side, however, the Broadway wing of the building will be a fairly close imitation of Furnald Hall to its north, though without the old-fashioned details such as carvings. It has been promised that the entire building will use high-quality materials such as the same kinds of granite and limestone as the original campus. A computer-generated video clip simulating a walk through the building. The architect of this building is Bernard Tschumi, Dean of Columbia's architecture school and a leading French architectural theorist. He is the author of The Manhattan Transcripts and Event Cities, a recent show at the Museum of Modern Art. His only built works are some buildings in the Parc de la Villette in Paris. CONSTRUCTION UPDATE: As of March 20, 1997, the basement slab is finished and the underground utilities are complete. A company called Helmark Steel from Pennsylvania has manufactured the building's steel frame, which is currently taking shape like a giant erector set. A French engineering firm is working on the design of the big glass wall, which will employ technology similar to that of I.M. Pei's famous pyramid at the Louvre. The main construction crane is in place. CONSTRUCTION UPDATE: As of February 20, 1999, this building is nearing completion and looks uglier by the minute. The Broadway facade is fairly polite to its historic context, but the on-campus side looks much louder, glitzier, clumsier and more aggressively high-tech than any of the drawings. The giant truss behind the main windows looks like a huge piece of construction equipment accidentally left behind on campus. It screams for attention on the tranquil plain of South Field so obnoxiously that it actually makes the banality of its predecessor look like discretion. CONSTRUCTION UPDATE: As of August 8, 1999, the promised roof has indeed shriveled, resulting in a silver-gray shed on top of the building that harmonizes with nothing and looks like an afterthought by an architect who forgot to leave a place for the air-conditioning machinery. The glass wall has turned out to be of low quality, having a greenish tinge and visual distortion that spoils the view from inside. Mr. Tschumi should never have been allowed these gauche avant-garde hi-jinks in such a sensitive locale. This building is simultaneously offensively inharmonious and dismally dull. There is nothing in its design you couldn't find in an upscale strip mall in New Jersey, which just goes to show the truth of the old saying that there is nothing more boring than the bad avant-garde. It may have been a fine ego-trip and career move for one Parisian ex-Marxist, but we will have to live with it for decades. Deconstruct your own quartier, professeur! UPDATE 12/20/99: This building is being widely panned in the architectural press. The Architectural Record did an unfavorable cover story in their November 1999 issue. City Journal did a story on how it epitomizes Columbia's gradual destruction of its historic campus, saying that Lerner, "...is an agitated, irrational mix of limestone, brick, metal, and glass...giving the impression of an edifice on the verge of a nervous breakdown." Students widely report that the building is cramped (all that space wasted on an atrium!) and inconvenient to use, not to mention resenting the student activities fees that have been raised to pay for it. The interior is an icy high-tech stage set of glass, steel, bare concrete and ugly furnishings. Two views of the completed building.The notorious ramps.The great glass wall. More ramps. Interior Hall.

UPDATE 1/15/00: The building continues to get bad reviews. Herbert Muschamp, architecture critic of the NY Times, politely panned it thus: "The strongest feature of the atrium -- in fact, of the entire hall -- is the view of the campus from inside." Great building: it's nice when you can look at something else. Funny how views of traditional architecture are always prized! No-one will ever build something designed to afford a view of this thing. "Let's have a little riot. We'll start by protesting the willfulness of that great metal and glass wall." Willfully slammed into an historic campus with no regard for harmony. "...all that intricately articulated metal and glass raises expectations that the design does not fulfill. The structure looks like a machine. " Yeah, we know: machine for living in and all that. But didn't people conclude they don't want to live in machines? "Taken together with the high-tech wall, the overlooking ramps and windows, and Lerner Hall's security desk, the camera insinuates a sinister presence into the entire composition." Yes, and all that glass, steel, and raw concrete, together with those detention-center chairs, don't exactly help, either. "Lerner Hall's biggest weakness, however, lies with the notion that the use of architectural forms to generate events represents an original contribution to the making of social space." Tschumi thinks he's very original in this regard. Not. "...an opportunity was lost here to establish a less oppositional relationship between the academy (the campus) and the marketplace (Broadway)." Not to mention between a classical campus and this high-tech intruder. "Good architecture doesn't depend on historical awareness. But claims to originality can't be verified without it. Instead of challenging such claims, architecture schools today have become factories for manufacturing them. I can't imagine anything more detrimental to genuinely innovative work." Bernard Tschumi should go back to school for a few years. "Lerner Hall doesn't reflect an architectural way of thinking. Form, structure, space, image, context, function, symbolism and social intention have not been synthesized into an esthetically persuasive whole. Tschumi has described his approach as cinegraphic. But good movies tend to have a sounder sense of structure -- a better architecture -- than we see here. Quite possibly, Tschumi will one day design a building that reveals original thinking about the relationship between buildings and events. At Lerner Hall, however, that glass atrium could symbolize the plight of an architect trapped in an elaborately staged conceit that the day is already here." Classic modern art: theory, posturing, and technical incompetence.  UPDATE 3/15/00: This building has garnered its worst review yet, in Metropolis magazine. Philip Nobel writes: "By now we all know that Bernard Tschumi's Alfred Lerner Student Center at Columbia University, open since late last August, is a dud." "... Students are nonplussed. One recently likened its central feature, a pile of glassed-in ramps, to an ant farm." "... When Lerner's Flemish-bond brick skin first appeared, aping adjacent classical buildings, all of New York Architecture whispered in unison: 'This is going to be a big embarrassment for Bernard.'" "... The problem is in the terms that Tschumi has set for his career... he fought the realities of the project to meet the demands of his place in the star system. He chose to crusade for the opportunity to pull off the sort of flourish that made his name... The result is a sort of star-system implosion, a messy, fizzled supernova." "... there was always a lingering sense among students [at Columbia's architecture school, where he is dean] that Tschumi was using the school as a means to advance his career, not as a platform for teaching. Under Tschumi, Columbia has become a machine for pumping out star architects: not problem-solving thinkers, but posturers; this season's splash and the nexts's flash in the pan. The trouble Tschumi got into at Lerner has its roots right there... It is clear that an undue amount of Tschumi's energies, and by extension the project's budget and manpower, went into realizing the structural overindulgence of the atrium... One designer at Gruzen Samton Architects, the bread-and-butter New York firm that Columbia retained to coauthor the building, says that Tschumi's focus on the atrium 'sucked all the life out of the building.'" "... The trouble with such two-faced contextualism is that it does nothing well: if you are trying to make a building fit in, why not fit it in proudly and fit it in well?"  Update 4/14/00: Another bad review, in Columbia Daily Spectator. Excerpt: "...while disjunction may serve as a theoretical point of departure, disjunction in a work of architecture’s formal composition or between an architect’s ideology and his constructions is a disappointing destination." (Full Text).  The real question is whether Columbia has learned its lesson. It may have, if only because this building went millions over budget, a fact that did not make the administration happy.Bernard Tschumi's own web page about this building.  A letter to the Architectural Record from a local resident about this building: Columbia's New Lerner Student Center Is A Monstrosity " I would like to add a voice from the surrounding community to your wisely unimpressed review of Columbia University's new Lerner Student Center. This building is an aesthetic and functional disaster about which I have not heard a single favorable comment from the students who use it or residents of the surrounding neighborhood. " Aesthetically speaking, its only redeeming characteristic is its Broadway wing, rumored to have been designed under strict traditionalist orders from the Columbia Trustees. But it looks as if architect Bernard Tschumi did as little as he could in this direction while aiming to get away with as much postmodern fun-and-games as possible. It is marred by snide postmodern gestures, like the absurd, useless, unprecedented recessed balcony and the use of glass brick rather than granite for the curved ledge above the second floor, which seem to mock the traditional archetypes on which it is based. It is as if the architect wished to make quite clear that even though he was forced to use such a style, he doesn’t really believe in it. This kind of coy, smirking irony has deserved acquired a bad name in recent years. " The section of the Broadway facade that makes the corner at 114th St is hideous. It is a naked lump of raw concrete bricks, glass blocks, and a weird and sinister stealth-bomber black brick with no precedent in the neighborhood. It resembles nothing so much as a high-tech minimum security prison. It disdains to respect the example of the splendid historic buildings around it, but does not establish by this rebellion a meaningful or interesting aesthetic of its own as an alternative. New York's Guggenheim Museum has tempted an entire generation of architects who are not Frank Lloyd Wright into thinking they are fit to design context-flouting buildings. Columbia is lucky enough to possess an historic campus which is one of the masterpieces of American Beaux-Arts design. New buildings built in the main area of campus should be in harmonious and historic style. " The other, or campus, side of the building is not just flawed; it is an unmitigated horror. It manages the amazing trick of being simultaneously offensive and dull. There is absolutely nothing in its design that would look out-of-place in a fancy strip-mall in New Jersey. Which part is supposed to be clever, the creation of this great postmodern architect whose theoretical writings are the toast of the intelligentsia worldwide? The entrance? I say, Bed, Bath & Beyond, route 85 in Mahwah. The roof? Home Depot, East Rutherford. The east wall? Maybe a welfare office in downtown Newark. Somebody once said there is nothing so unoriginal as the bad avant-garde. " The giant, garish, silver, heating-and-air-conditioning shed on top of the building is simply inexcusable. It looks as if the architect simply forgot about the need for this, and tacked it on at the last minute when someone reminded him, hoping no-one would see it. But there it sits, in full view of everyone on Low Library steps, Columbia's most celebrated vista, looking like a giant tractor-trailer full of refrigerated fish. It is a mark of the very lowest type of commercial architecture to have its utilitarian necessities merely stuck on, unintegrated into the design. " The only faintly interesting part of the exterior is that giant energy-wasting glass wall on the north side, which looks as if it’s just about to fall off and whose unconcealed and bristling hardware looks permanently unfinished. The uneven glass has a sickly greenish tinge that looks cheap and creepy and spoils the view of campus. The fact that part has already cracked does not inspire confidence, either – technical competence is a bare minimum from which no-one is exempt. The ramps behind it, in their harsh unpainted steel, look like nothing so much as a giant multilevel assembly line in an automobile plant. Their configuration is weird and their staircases illogically placed. When they use them, students scurry along these ramps like rats in a cage designed by M.C. Escher. But mostly, these ramps don't even get used much, showing an elementary lack of understanding of traffic flow on the part of the architect. " For space to have been wasted on these ramps when student groups continue to go begging for room on America's smallest and most cramped major university campus, is simply inexcusable. The east wing could have been another two stories higher without looking any worse, and might indeed have looked better, as this would bring it up to the level of the adjacent Butler library. But after all this fuss, the building isn’t even big enough, and this potential extra space will probably be lost forever. Columbia will continue to be handicapped among top universities in its efforts to fix its notoriously under-developed student life. " The interior is marred by unnecessarily forbidding touches like garish rotating bars at the Broadway entrance that scream to every visitor what a dangerous place Manhattan must still be; less brutal-looking hardware is readily available. There is nothing in this building’s interior that is warm, or welcoming, or that suggests in any way at all the “home away from home” that a student center should be. It is all raw concrete, steel, and fixtures coldly fit for a corporate headquarters. At night, it has a high-tech creepiness that borders on a science-fiction aesthetic. It is gray. The architect's nonsensical assertion that "the students will provide the color" is a pure abdication of aesthetic responsibility, or a confession of failure. " Mr. Tschumi has delivered this monster with all kinds of intellectual bombast about "deconstruction” and the other trendy philosophical buzzwords that dribble from postmodern architects’ mouths like so much pig Latin. He has attempted to paper over the building's obvious flaws with implausible rationalizations: your reviewer quite sensibly blew the whistle on his scam of claiming that the atrium "reads like a void, echoing the other spaces on campus." The attempt to substitute rationalizations for aesthetic achievements is squarely in the very worst tradition of modern art, as famously pilloried in Tom Wolfe's book The Painted Word. " In truth, this building is simply boring, pretentious, run-of-the-mill commercial architecture with absolutely no innovation, no originality, and no distinction whatsoever, and unworthy to be covered in, let alone be given the cover of, a magazine of your caliber. Perhaps its mixture of pseudo-intellectual bombast masking commercial banality is appropriate for contemporary Ivy-League undergraduates. One would hope not. This building is supposedly the masterpiece of one of the world’s great architectural theorists – for Mr. Tschumi's architectural reputation at the time of his being given the commission was based entirely on his work as a theorist – but is in fact a breathtakingly unoriginal piece of hack-work tricked up in fancy jargon to conceal its awesome mediocrity. Jacques Derrida goes to the mall. " If there is one lesson to be drawn from this building, it is never to allow an inexperienced architect, with no significant track record of built achievement, to receive such an important commission. For those that care, let the record state that the Morningside Heights Residents Association did protest to the Columbia administration in favor of a more traditional design for Lerner Hall, and that the architect met with two representatives of this group, including myself, and essentially ignored us. " So why was Bernard Tschumi given the commission? Probably, though this cannot be proved, as part of his compensation package for becoming dean of the Architecture School. Architectural commissions should be given to those who have proved that they know how to build, not as boosters for those who can’t seem to get their careers off the ground on their own merits. This is not necessarily corrupt, but it smacks of the way universities love to hand out teaching assistant jobs to people who can’t teach as a part of their doctoral fellowships. Either way, undergraduates and the community suffer. Only this mistake will last for years. Usually, them that can’t do, teach. If only it were always that way.

UPDATE 5/15/01: The Blue and White, a Columbia student publication, has panned Lerner as follows:

"Understanding Lerner Hall

by Daniel Immerwahr

Event-Cities 2. By Bernard Tschumi. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2000. 692 pp. Paper, $35.00, ISBN 0262700743.)

Last year, the Columbia student body received, with much fuss and to-do, a new student center. This year, that same student body can read about this project in a book recently published by Lerner Hall's architect, and Dean of the Graduate School of Architecture, one Mr. Bernard Tschumi. As architectural fluff books go, Event-Cities 2, Tschumi's 692-page brick/book, is rather cheap, although I suspect that its hefty price tag ($35) puts it out of the reach of much of the student body. This is unfortunate, as one of the chapters of the work is dedicated to Lerner Hall, a significant building in the lives of many Columbians. Event-Cities 2 is Tschumi's attempt to pitch his work to his fellow architects and architectural critics, as well as to future clients."

"In an attempt to respond to (or, better put, dismiss) critics of the building, Tschumi offers this: "This project is about a building that was alternatively praised and attacked for the wrong reasons. For example, 'conservatives' derided its large expanse of glass as heresy within the historical context, while some 'progressives' said its use of 'mimetic' granite, bricks, and cornice was a disgrace to the ideas of progress, newness, and creativity." Regardless of whether or not we buy into Tschumi's very reductive reading of the architectural criticism of his work (which lets him position himself comfortably as the smiling iconoclast), it is worth pointing out that there is another source of criticism that is completely ignored: that of the actual occupants of Lerner Hall."

"The lack of concern for the students (and staff, administrators, guests, etc.) for whom this student center was designed runs throughout Tschumi's commentary on his work. To whatever degree the people using the building figure into Tschumi's conception, they are "forces" whose movements are molded into patterns that are as much a part of the architecture as the building itself. As Tschumi writes, Lerner is "not about forms, but about forces" -- a thought one should keep in mind when navigating the poorly-planned aggregation of ramps and stairs that are required simply to get to one's mailbox. We can take comfort in the knowledge that, at night, our bodies on the ramps form a sort of "silent shadow theater" for those in the know."

"These sort of comments from Tschumi should lead us to question the motives that drove the design of Lerner Hall. For whom was it built? Clearly, Tschumi was interested in producing something that could function as a thought-provoking and exciting architectural project. This is why, for Tschumi, the "critics" are the architectural cognoscenti, the kind of people who could, with some semblance of a straight face, call Lerner's glass wall "heresy." However, we must remember that Tschumi was contracted to build a student center, not a vanity project. We should ask why the stage is so ill-suited to performance pieces (the dance group Orchesis entitled last year's show "Zero Degrees" in reference to the lack of incline in either the stage or the seating). We should ask why the administrative area of the building, conspicuously unmentioned in Event-Cities 2, is such a labyrinth. We should ask why we needed a "softening committee" to mediate between the students and the sterile building when Lerner was first opened. We should ask why, in a university that has had so much trouble relating to the neighborhood it occupies, the Broadway façade of Lerner takes on the look of a fortress."

"Of all the questions we might ask, perhaps the most important one is about Lerner's price tag. From an administration that is quick to inform us that the expansion of teaching staff or of much-needed classroom space is not on the immediate agenda, $85 million is an almost ludicrous sum to spend on a semi-functional collage of glass and brick. To a certain degree, we should be invested in the kind of aesthetic statements our architecture is making, but is this a priority worth $85 million? How much are we getting out of Tschumi's gigantic glass wall, made of 800-pound sheets of specially-fabricated glass? How much do we need clusters of expensive leather chairs at the end of every ramp? While I realize that much of the money for Lerner Hall has been raised specifically for the project, including from Mr. Alfred Lerner himself, who coughed up a cool $25 million, was this the best aim of our university's fundraising efforts? What about scholarships, neighborhood initiatives, funding for student events, or even pay raises for our overworked junior faculty and teaching assistants? With so much at stake in a building of these proportions, we are justified in demanding an explanation for some of the choices that directed the Lerner Hall project, and this is just what is lacking, both in Event-Cities 2 and in all of Tschumi's public statements that I've come across about the project. This lack of public response is especially jarring when one considers that Tschumi, who associates himself very closely with the French student

uprisings of 1968, "les evenements du mai," seems to have, while still talking the talk, walked right on over to

the other side. Lerner, more so than the buildings of the McKim, Mead and White plan, exerts a top-down

control on its inhabitants. The ramps are uncomfortable, and rather than encouraging a "contamination of

activities," as Tschumi suggests, they force students into awkward circulation patterns, and often remain totally

empty. Notre lutte continue. Lerner Hall, and Event-Cities 2, are both done deals. As time passes, and as the quickly-changing college population forgets the construction of Lerner, it will also forget that there were other possibilities. Just as

students on this campus do not gripe about the imperialist architecture of the original McKim, Mead and White

plan, they will soon learn to accept Lerner Hall as just another piece of the unchangeable landscape. Thus, with a nod to the inevitable, we tip our hat to Tschumi, he has foisted another one on us. He can go back to his work

on Event-Cities 3: My Life as a Rebel, and we can go back to the unfeeling structure that is our student center,

and wait for a storm." (See original.)

UPDATE 7/2/01:The respected periodically-issued book New York: A Guide To Recent Architecture had this to say about Lerner Hall in its latest edition: "Oh dear. The first American building by Bernard Tschumi has turned out to be a bit of an architectural fiasco. Tschumi's career as dead of the Columbia School of Architecture makes the universal panning of the building all the more painful. The radical building promised by much of his writing turned out to be far more exciting in prose than in reality... What explains the 1980's dentist office glass block, imitation limestone and fake copper? Tschumi's so-called strategy - 'a quiet building on the outside and a stimulating building on the inside' - seems to have resulted in just the opposite. The confused, pastiched facades never really gel on their own, let alone with each other. The list of inconsistencies and sloppy design details goes on and on, sadly trivializing any revolutionary effect. One can only imagine what Tschumi the theoretician would have said if presented with a model of Lerner Hall by a student" (p 13.4)

UPDATE 8/3/01: Lerner Hall and its architect have attracted the (negative) attention of a webzine. See Robert Locke's article in FrontPage magazine.

Other Major Projects | Home | Next |